Satellite navigation is precise, reliable and available continuously around the globe, but overreliance on it presents a clear and present danger to the smooth passage of maritime trade, concludes a major ESA-backed study.

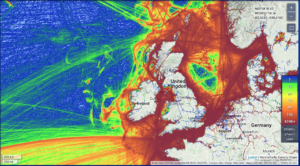

With seaborne trade projected to double by 2030, the MarRINav project used a simulation approach to ‘stress test’ current navigation methods along highly trafficked shipping lanes around the British Isles. Every day more than 1.36 million tonnes of cargo arrive at major UK ports, guided predominantly by signals from space.

“Traffic complexity and density continues to grow around British waters, and shipping increasingly has to share the sea space with other users such as offshore renewable energy installations and conservation areas,” says Jonathan Turner of ‘blue economy’ specialist NLA International, which led the study for ESA.

“The aim of our Maritime Resilience and Integrity in Navigation, MarRINav, project, was to peer 10 years ahead to see if the needs of mariners for accurate, resilient ‘positioning, navigation and timing’, or PNT for short, would continue to be fulfilled.”

What the MarRINav team found was that the very success of satellite navigation, in terms of its precision, reliability and always-on availability, is a cause for concern.

“The issue we ran into is that satellite navigation is today the primary – and sometimes only – marine aid-to-navigation, even above looking out of the window,” adds Jonathan Turner. “This has happened without any conscious policy decision as such but simply because of satnav’s technical excellence, available on an open source, global basis. The underlying problem is that the signals from the satellites are extremely weak, and therefore prone to environmental as well as deliberate interference.”

With the signals’ intensity being equivalent to light from a 60-watt torch shone thousands of kilometres down from orbit, disruption can occur due to solar storms and other space weather, or else local interference such as ‘multipath’ reflection off port buildings or other fixed infrastructure. And the UK’s Trinity House has demonstrated the vulnerability of ships to satnav jamming and spoofing – testing in the North Sea showed vessels could be fed false positioning data without any alarm being raised.

The key topics MarRINav focused on were PNT ‘integrity’ – that users can be warned promptly when a navigation service is not reliable – and ‘resilience’ – the ability to recover rapidly from any disruption.

In studying UK maritime traffic, the MarRINav team were guided by International Maritime Organization (IMO) guidelines for navigation, requiring a minimum of 10 m positioning accuracy in the open sea and 1 m accuracy in coastal waters.

The team found for instance that some ports on the coverage edges of Europe’s satnav-augmentation system EGNOS experience brief periods of degraded positioning – down to the fact that the system is optimised for aviation rather than maritime users – that may be possible to overcome if specially-designed maritime receivers are employed.

They also estimated a five-day interruption in satnav coverage would cost the UK’s 10 largest ports some £601 million, projected to impact upwards of 5 200 vessels.

Such an outage would have counterintuitive outcomes: satnav underpins many ship systems beyond simply the main bridge-based Electronic Chart Display and Information System employed by navigators. For example, satnav feeds into positioning data transmitted by Automatic Identification System transmitters, sets ships’ clocks, and even helps calibrate onboard gyrocompasses.

Back on shore, port cranes can shut down during satnav outages, as experienced at the Israeli ports of Haifa and Ashdod last year.

“Our team talked to mariners, port operators, maritime and navigation experts, and shipping customers around the UK and Ireland,” adds Jonathan Turner. “Our conclusion is that there is no single system that can replace satnav. Instead we propose a ‘system of systems’ approach, blending multiple PNT sources as required, to be implemented through a new Multi-System Receiver whose requirements have been defined by the IMO.”

Proposed sources for this receiver comprise:

- Terrestrial radio-navigation system eLoran, with new infrastructure to enlarge its coverage

- The coming VHF Data Exchange System – Ranging mode, which will include the current AIS

- identification system as a key component

- Radar-based absolute positioning

- Dead reckoning based on onboard inertial measurement units

- Terrestrial positioning system Locata for portside navigation

- Multi-constellation satnav, including the coming EGNOS v3, with potentially a dedicated EGNOS maritime service.

MarRINav received support through ESA’s Navigation Innovation and Support Programme (NAVISP) Element 3, which focuses on national navigation priorities of participating Member States. The team’s next steps are to engage industry and the public sector to realise the report’s goal – resilient future PNT for UK mariners.