Doresa and Milena, the fifth and sixth Galileo satellites, have been in a safe state since 28 August, fully under control from ESA’s centre in Darmstadt, Germany, despite having been released on 22 August into lower and elliptical orbits instead of the expected circular orbits.

The potential of exploiting the satellites to maximum advantage, despite their unplanned injection orbits and within the limited propulsion capabilities, is being investigated.

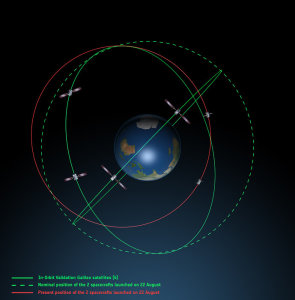

In these two views the Galileo-FOC FM1 and Galileo-FOC FM2 satellites’, launched together by Soyuz on 22 August 2014, orbits is represented. In red, present position, while the intended one is shown in dashed green and the position of the four satellites launched in 2011 and 2012 in solid green.

The “from above” view looks down over Earth’s South Pole. This figure helps to illustrate how the two satellites’ orbital inclination relative to the equator is less than was intended (55º).

This view looks side on to the two satellites’ orbital plane, which is off-centre relative to Earth. The satellites are in an elliptical rather than circular orbit, with a maximum altitude of about 25900 km and a minimum altitude of about 13700 km. This compares to a planned circular orbit of 23222 km altitude.

The satellites are in a safe state, correctly pointing towards the Sun, properly powered and fully under control of an ESA–CNES team.

The various ESA specialists, supported by industry and France’s CNES space agency, are analysing different scenarios that would yield maximum value for the programme and safeguard, as much as possible, the original mission objectives.

Marco Falcone, ESA’s Galileo system manager said his team has been working intensely to determine if the satellites can be at least partially recovered. Among the considerations are the flight dynamics of moving the two spacecraft and the impact of the radiation they are experiencing in their current location.

The radiation can shorten the satellite’s lifetime, said Falcone. “It’s very dangerous for the satellite.”

Other factors include flight dynamics and optimal re-orbiting and in-plane phasing given the limited propellant fuel on the spacecraft. ESA engineers are looking at expected user and ground receiver performance in light of the varying Doppler effects at perigee and apogee.

Another unknown is the timing performance of the satellites’ rubidium frequency and hydrogen maser given the relativistic effects of the eccentric orbit. Signal issues, such as the navigation message almanac, also must be considered before the FOC satellites can be introduced into operation, Falcone said.

More detailed analysis, alongside consultations with industry, is under way, checking for a potential “improved orbit” where they could both provide operational services.