With the first Galileo services set to begin this year, ESA is working directly with European manufacturers of mass-market satnav chips and receivers to ensure that their products are Galileo-ready.

“In coordination with the European GNSS Agency, we put out an open call to satnav manufacturers offering testing with our laboratory facilities. We have gone on to work with five mass-market chipset makers and a comparable number of professional receivers manufacturers” explained Riccardo de Gaudenzi, head of ESA’s Radio Frequency Systems, Payload and Technology Division.

Key facilities being used at ESA’s Navigation Laboratory include “Hybrid Localisation Solution Rack”, where receiver chips can be plugged in. This rack generates simulated constellations of Galileo, GPS and other satnav systems along with Wi-Fi or mobile networks which phone-based satnav chips often additionally employ.

Another resource is the “octobox”, a mini anechoic chamber into which phones or mobile devices can be placed, in order to feed them simulated satnav and cellular network signals.

Testing in the field is carried out with the Lab’s Telecommunications and Navigation Testbed Vehicle. This fully equipped van carries its own extremely accurate receivers to assess the performance of the consumer items being tested.

Whether they are being used for vehicle navigation, shipment navigation or precision agriculture, the performance of satnav terminals comes down to the specialised chips embedded within them. The same is true of mobile phones, although their chips tend to be optimised for low-power, high-sensitivity operations.

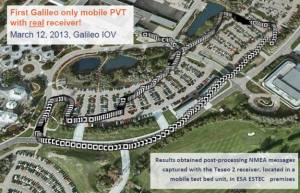

“Thanks to earlier collaboration with ESA and the EU, the millions of multi-constellation satnav chips we sell annually have been equipped for Galileo signals since 2009. It will take only a software update to enable them to start using Galileo” commented Philip Mattos of ST Microelectronics, whose Teseo-2 receiver chips are used in satnavs and embedded in cars.

Combining radio frequency and silicon elements, a single 1 cm sq chip can detect signals from multiple satellite constellations (Galileo, GPS, Glonass and Beidou) then convert them into precise positioning measurements.

Beamed across thousands of kilometres of space, the signals are incredibly faint, barely distinguishable from background noise. But a technique called “correlation gain” synchronises them with copies of each satellite’s broadcast code stored in the chip’s memory to boost them to usable levels.

For mass-market single-frequency designs, an ESA-created ionospheric model allows the subtraction of ionospheric delays, its performance coming close to dual-signal standards.

Chips also apply stored ephemerides data embedded in satellite signals, updates on where satellites are positioned in the sky, to speed up acquisition times.