Three new stations have been deployed on three islands at the far corners of our continent, ready to pick up distress calls via satellite from all across Europe and its surrounding waters.

These stations sit on Svalbard in the Norwegian Arctic, Maspalomas on Spain’s Canary Islands, and Larnaca on Cyprus, forming a triangle enclosing Europe. The three are coordinated and overseen from a control centre in Toulouse, France.

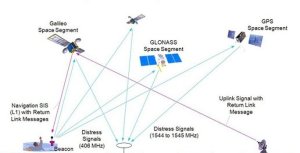

Each site is equipped with four antennas to detect distress calls relayed via satellites in medium-altitude orbits, so far including 14 GPS satellites, two European Galileos and one Russian Glonass.

The three stations are interlinked to operate jointly, so that all 12 antennas can track satellites together. A summer of testing has confirmed the heightened efficiency of this approach.

Cospas–Sarsat’s extension to MEOSAR (Medium Earth Orbit Search and Rescue) will extend its search and rescue coverage (the area outlined in red)

“This new search and rescue infrastructure, designed by ESA and financed by the EU as part of Galileo, is our contribution to the Cospas–Sarsat system, the world’s oldest and largest satellite-aided rescue system,” explains ESA’s Fermin Alvarez Lopez.

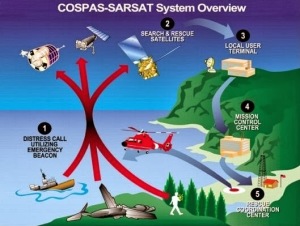

Founded by Canada, France, the USSR and the US, Cospas–Sarsat is a global satellite system for rapidly detecting distress calls to be forwarded to local search and rescue authorities. Since its creation in 1979, it has helped to rescue more than 35 000 people.

Cospas–Sarsat distress beacons can be bought off the shelf, then activated by anyone in distress on land, in the air or on the sea. Satellite repeaters pick up and amplify the beacon signals, then transmit them down to ground stations.

These stations identify the approximate location of the signal and then pass the information to the rescue authorities.

“Up until now, Cospas–Sarsat has relied on satellites in low and high orbits, but medium orbits with satellites such as Galileo are better: they combine a wide field of view with strong Doppler shift, making it more likely a distress signal is pinpointed promptly and accurately” adds Alvarez Lopez.

The broad coverage also means fewer ground stations are required – hence just three can handle the entire European service area.

Once the stations were completed, testing began, Igor Stojkovic, ESA’s search and rescue engineer explains: “We have been demonstrating the system performs as required, ahead of handing it over to its operator, part of France’s CNES space agency, in December ahead of service beginning in 2016.”

Like the US GPS and Russian Glonass, European Galileo satellites will carry Cospas–Sarsat MEOSAR (Medium Earth Orbit Search and Rescue) transponders. Galileo will also offer ‘return link messaging’ so that, for the first time, those in distress will receive replies confirming their call has been picked up and help is on the way.

Distress beacons emit UHF bursts every 50 seconds. The stations are required to detect and locate all signals received to within 5 km after 10 minutes.

“With all three stations working together we’ve demonstrated significantly better performance than requirements,” comments Francesco Paggi of Thales Alenia Space Italy, working on the qualification. “So all signals have been detected inside the service area within a minute, with 99% of test localisations performed to less than 5 km, and 79% within 2 km, after 10 minutes.”

“Then these localisations are automatically passed on to regional Mission Control Centres within a minute and a half for forwarding on to the closest search and rescue agency.”

Illustrating the system’s responsiveness, automatic distress signals from two recent tragedies were detected rapidly during the qualification: the crash of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 in Ukraine in July, and the collision of two Italian Tornado jets the following month.

“The accuracy of localisations increases with the number of satellites actually used, because the stations perform the same kind of ranging used for satnav services, except in reverse – with somewhat reduced precision because the beacon signals originally designed in the 1970s were not optimised for ranging from medium orbits” Stojkovic explains. “So as more equipped satellites go into orbit, the performance should get even better.”

A set of reference beacons is now being added for continuously monitoring the system’s performance.